100 years of Functionalism in the Czech Republic – the Ensemble Legacy

Only a few years ago, the Czech Republic celebrated its 100th anniversary. Functionalism is closely linked to the emergence of the country. In Zlín in Moravia, the entrepreneur Tomas Bata not only turned his shoe company into a global corporation, but also had a lasting impact on the city, making it the first functionalist city in the world.

The higher you go, the clearer the urbanisation of Zlín becomes, and it doesn’t get any higher than this. Dr Zdeněk Pokluda and I are standing on what was once the tallest building in what was then Czechoslovakia. The Administration Building No. 21, also known as the Bata skyscraper, was built here between 1936 and 1939 and was one of the first high-rise buildings in Europe. The historian Pokluda worked for many years as Director of the State District Archive in Zlín and researches the Czech economic history of the 19th and 20th centuries. He specialises in the Bata company, which rose to become the largest shoe company in the world in the first decades of the 20th century and whose dominant market position is closely linked to the businessman and industrialist, Tomáš Bat’a [Tomas Bata].

Pokluda describes Bata as a “self-made man, as his name is almost symbolic.” This is because Bata gave Zlín “the reputation of a city of gardens and modern architecture, the face of which it has retained to this day.”

From the roof terrace of high-rise building no. 21, the native of Zlín explains this functionalist appearance, which is only 100 kilometres away from Brno, the other important site of Czech Functionalism. He points out the stringent structure of the factory complex with the numbering visible from afar, the workers’ housing estates and the solitary buildings such as the market hall, the multi-storey department stores, the large cinema and the halls of residence. Another striking feature is the topography of the city with its hills and the elongated depression, intersected by multi-lane roads. Seen from above, the streets Gahurova and No. 49 or Tomáše Bati Road run through the town like logical, linear solutions. This makes them an ideal match for Bata’s industrial brick architecture. Serial efficiency and growth-orientated productivity were dovetailed in the manufacturing processes as well as in the construction of the factories.

The Tomas Bata story begins in 1894, when he founded a shoemaking workshop with his siblings Antonin and Anna. He later managed the business alone and built it up into a shoe empire, which eventually became a conglomerate with chemical, food and textile production, as well as a rubber and paper manufacturing division. At its peak in the 1920s and 1930s, the company employed over 60,000 people worldwide.

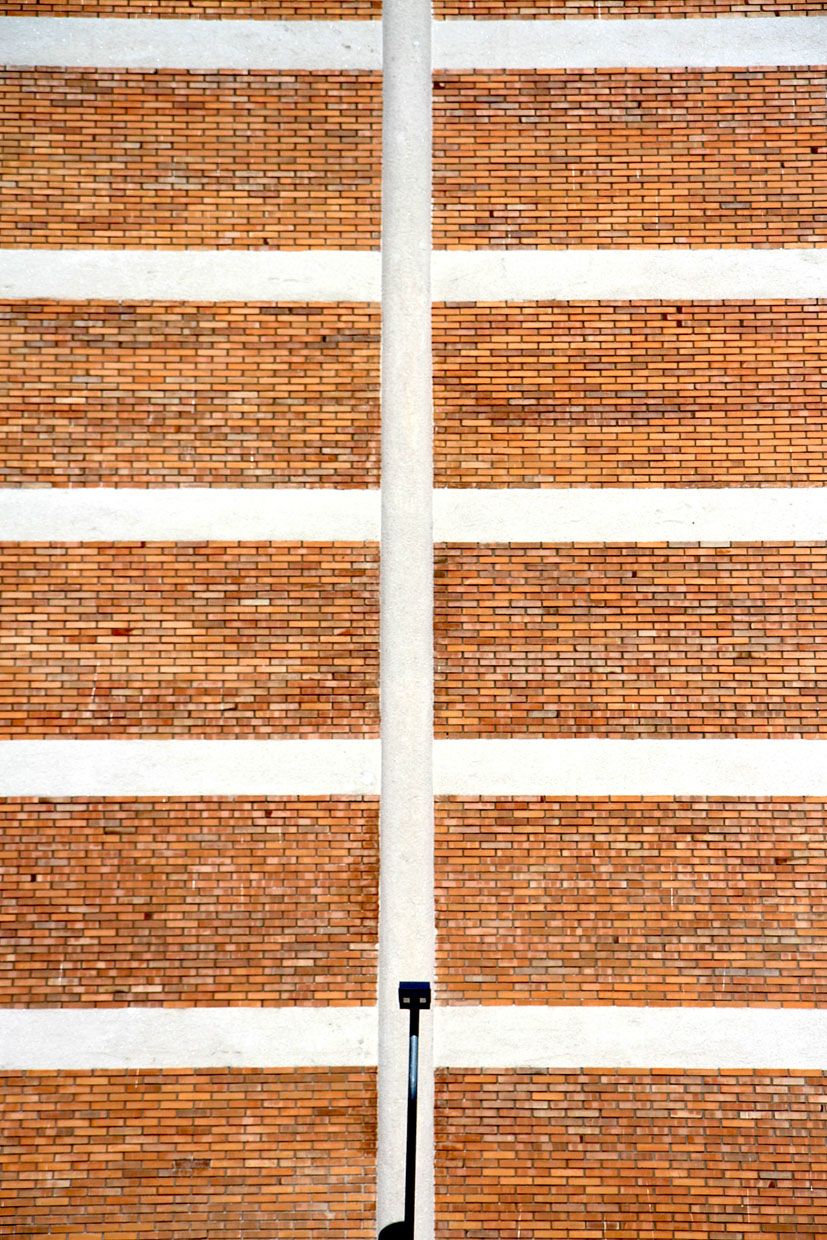

The unrendered brickwork with large, divided windows became the hallmark of the uniform appearance of Bata architecture in Zlín. The standardised industrial buildings were laid out in a chessboard pattern, grouped into larger ensembles and connected to each other via transport systems. Standardisation reduced costs while at the same time speeding up construction times. Several architects were involved in the development, including Jan Kotěra (1871-1923), František Lydie Gahura (1891-1958) and Vladimír Karfík (1901-1996). All three symbolise the different phases of the Bata era. Kotěra, a student of Otto Wagner from Brno, designed the first housing estates and as a university teacher, he influenced the next generation of Czech architects, for example when he taught Bohuslav Fuchs.

The tower block designed by Karfík is one of the most important works of Czech Modernism. With its height of 77 metres, it was the tallest building in the country for a long time. As with the production buildings, it is based on the same modular system of 6.15 metres x 6.15 metres. The supporting structure is made of reinforced concrete, the outer wall consists of the characteristic divided windows and brick infill. The Bata Works administration building survived the Second World War unscathed. It was renovated in 2004 and is now the seat of the Zlín Regional Finance and District Office.

This change of use also symbolises the transformation not only of the Bata site, but of the entire city. After the Second World War, the new communist rulers portrayed the Bata family as exploiters and enemies of the people. The successor company went bankrupt. The Bata heirs in Canada, on the other hand, were successful with their new start. Today, Bata is a corporation with 30,000 employees based in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Zlín today lives and works with the Bata gene. Those responsible are aware of the unique European heritage of the ensemble. At the same time, it is facing up to the new era, which appears to be an elliptical glass-and-metal century in the form of the Culture and University Centre (KUC), designed by Eva Jiřičná (b.1939). Born in Zlín, the award-winning architect lives and works in London. She returned to her native city for the KUC and created two large, elliptical bodies that together form a V, making the forecourt an inviting gesture towards the Bata area. Another feature is the thorn-like roof crown of the cultural centre and the glass screens on the facade.

These shapes and materials: was there any controversy in the city? “No, not at all,” says Pokluda, the Bata and Zlín expert. “It was discussed, but people realise that they can’t shut themselves off from the new era.”

He talks about the migration of young people to Prague, the structural change in the region and how to deal with the functionalist heritage – in a contemporary way and with respect for the Bata era. It is fitting that a school, designed by Gahura, stood on the same site, also with several buildings that form a forecourt opening onto the city. A city could not face its functionalist heritage in a more considered and contemporary way.

Text / Photos: Jan Dimog

Note:

Hej rup (Let’s go), a survey exhibition on the Czech avant-garde movement, can be seen at the Bröhan Museum in Berlin until March 3, 2024. An exquisite show, as Oliver G. Hamm judges in Bauwelt 3/2024. Our author also highly recommends a visit!

Author info:

Architect Hendrik Bohle runs a digital magazine on building culture together with journalist Jan Dimog. On thelink.berlin they have been telling about their discoveries in Europe for years, especially about the connections between people and architecture.

When they are not on the road, they curate high-profile exhibitions, such as the travelling exhibition on Arne Jacobsen’s architecture.

One Comment

Dank für den Hinweis auf thelink.berlin. Die Adresse wird uns ein interessanter Begleiter auf unsren Reisen mit dem VW-Bus sein