Anarchy requires a sense of duty: Peter Haimerl

We interviewed one of Bavaria’s most renowned architects about freedom and responsibility, skills (also ones that are lacking), the architectural world’s comfort zone and the future of living in honeycombs.

Let’s start by saying that we’re missing the Schedlberg house in our portfolio. What’s in the pipeline for the house now?

Renting it out just as a holiday home has proved tricky. Therefore, I’ll be organising more Schedlberg academies or increasingly offering it as a thinking space. Nowadays, everything revolves around target groups and their expectations. Online searches are all about hashtags. But the Schedlberg house is more complex and a place you need to experience. It’s stark, rustic and lacks any frills. Relating to it requires the right mindset.

Margit Ulama, who organised the Turn On architecture festival in Vienna, was recently a guest. But the core problem remains. Architects and fans of architecture are usually impoverished. And the house is too minimalist and basic for those who do have money.

My problem is that I don’t want this level of comfort –

so no design, no whirlpool or this supposedly fabulous furniture.

We’ll see what the future holds. I’m currently planning an even crazier holiday home in the Bavarian Forest for a client. But guests will probably like this house more because it’s not quite so sparse.

Your projects that we’re familiar with are all in Bavaria. Have you ever built anything outside Bavaria?

Sure, in Cincinnati for instance. One of the city’s parks features my Castle of Air pavilion and its awesome mirrored facades.

And you probably also receive lots of enquiries for projects, even outside Bavaria?

I very rarely receive enquiries about projects. I proactively seek out projects in places I’d like to transform and have an immediate vision for. The concert hall in Blaibach is the best example.

If I waited for projects,

I’d be dead.

I sought out the mayor and told him that his village was run down. My offer was to take part in a state competition on behalf of the village and waive my fee. But I imposed two conditions. Firstly, I wanted free rein to do as I liked in the competition and secondly, I was to be made planner if the village won. The mayor agreed, unaware of what lay ahead.

My maxim was that I was looking for people, not practising architecture. I spent a year in Blaibach and talked to 50 people, individually or in groups.

That’s how I found Thomas Bauer, whose idea was to build a concert hall. We went to the local council and announced we were going to build a concert hall. The council applauded the idea but had no extra funding to offer. And said it could cost no more than the car park they would have built in the same location. Which was slated to cost four hundred thousand euros. So I promised I’d build the concert hall for that amount. In the end, it cost the council five hundred thousand euros.

Thomas Bauer received no money and had to put up a guarantee of one hundred thousand euros at the beginning. He pays the concert hall’s heating costs and personally organises a concert programme costing 1.2 million euros every year.

But the whole project must have cost more than five hundred thousand euros surely?

The construction costs were 2.5 million euros gross – including the outdoor facilities and all ancillary costs. Thomas Bauer and I managed to obtain subsidies from the state. My studio alone acquired about eight hundred thousand euros in sponsorship. Some 60 companies were sponsors and 60 tradespeople worked for nothing – all organised for free in six months.

That’s how we did it in Blaibach. Nobody wants to hear the story, but it has to be told and that’s how we pulled it off.

Most of your colleagues wouldn’t do that, what do you say to them?

Yes, I understand. We had that same discussion in the office every day. Lots of them counter that I don’t earn anything. And it’s true that I pay extra for lots of projects – Blaibach is no exception.

But I always stop and think who would have the chance to build a concert hall in a village in the Bavarian Forest. Or a subterranean concert hall in the north of Bavaria.

Who would build the Schedlberg house? Nobody. And, of course, projects like Blaibach are something of a page-turning novel. Ventures requiring a touch of lunacy. Because undertaking them requires you to be something of an adrenaline junkie.

But ultimately the novel does have a happy ending?

Absolutely. The venue recently featured Micha Friedmann talking to Igor Levit about love, swiftly followed by András Schiff giving a fantastic piano concert and then a guest appearance by Japanese conductor Kent Nagano. The hall has been sold out for 10 years. Our programme is on a par with any in Munich. And the hall has capacity for 200 people.

And if someone were to approach you with a commission, what area would interest you?

Initially, that’s not important. Nowadays, I do things completely differently anyway. If someone contacts me, I conduct a client audit first. That’s the starting point.

It’s usually couples who come to us with a project. My wife draws up a script for two days, detailing the moment they get up to when they go to bed. The script covers everything – what they wear, the music they listen to and what they do in the process, how they engage with and what they say to one another. Nobody would think of telling a composer how to create a piece of music after all.

By the way, the first condition of the audit requires clients to trust their architects who will save them from having what they want.

That might sound a little arrogant, but I’m fed up with this insanely amateurish approach to architecture.

You called your talk at Architects not Architecture Anarchy and Freedom at the time. Where do these freedom-loving characteristics of yours stem from?

I come from the Bavarian Forest. Which was always somewhat out in the sticks. Nobody went there of their own free will, only those who hadn’t made it elsewhere.

And, of course, local government officials who were transferred to the Bavarian Forest from Munich. Which meant that two types of people clashed with one another. On the one hand, you had the sluggish, non-conformist types and on the other, civil servants who could also be ruthless. Consequently, a basic anarchist mindset has traditionally evolved over the centuries. This manifested itself in a usually comical and, above all, very individual way. In truth, everyone had to muddle along somehow and develop a philosophy. Which is also apparent in the construction style. Everybody developed their own house, which was just like other people’s. Over the centuries, a kind of recycling aesthetic evolved that followed certain rules. And a touch of humour was required to make this aesthetic bearable.

For instance, there’s a spot at the Schedlberg house with stacked pieces of wooden beams – which is completely absurd of course. The Waidlers (editor’s note: the name of Bavarian Forest locals) were very skilled woodworkers. Which makes you question why they did things like that nevertheless.

Because their standard retort to neighbours questioning the method behind this madness would be “Oh, so you’ve noticed then?” It’s a completely different attitude. In this case, architecture is a type of sarcasm whose purpose is really just to perpetuate this marginalised, sluggish society.

Which is why the Bavarian Forest’s story is ultra-modern because it’s precisely the issue facing us.

We have an incredibly diverse world and a concept of architecture that simplifies and rationalises everything until it’s reduced to purpose or function.

And that hasn’t worked for a long time.

In other words, give architecture and architects freedom – is that the message to the planners?

Architecture must, of course, meet fundamental needs, create spaces that stimulate people and that had never existed previously in that form. The underlying complexity is enormous and needs to be translated into images for each person and philosophy. I always call it our duty to be consistently restless.

We architects must stabilise society by being consistently restless.

Which is exhausting because of the huge responsibility it entails.

In that sense, freedom means doing everything as responsibly as possible. This type of anarchy requires a huge sense of duty. But I hate repeating myself. It’s boring. Architecture offers so many opportunities to not repeat yourself.

Changing the subject: how do you develop the extreme complexity in your projects – digitally or via models?

Ours was one of the first studios in Germany to start programming at the end of the 1990s. We’ve been doing everything in 3D for 30 years. Model building is not for us because it simplifies everything too much. To me, architecture is like a film or music. I do, of course, plan spaces via traditional concepts but more by using my mind’s eye.

You use renderings in a very understated way – it’s noticeable that the geometry is extremely precise. 3D stays 3D and not some kind of fake reality. Is that correct?

The crucial point is when the digital meets 3D. Perhaps I should tell you how I got into architecture in the first place. During my childhood, I always had one dream. It involved me asking whether an interface between the world of contemplation and the material world existed. At some point, I realised that it was very simple. When you code, you can create purely digital, mathematical worlds via vectors for instance. For example, I can dismantle a town that is build of stone or concrete.

In other words, I can say that the stone doesn’t exist, but is really just vectors. Or that streams are running through it and I use these streams, or streams of thought to model with. Which makes it all so amazingly fascinating because everything you think about, feel and construct is the same.

In my case, I stumbled into architecture more by chance. Actually, I was more interested in exploring philosophies and theories. They are what saved me.

Lots of people ask me how I pull off my projects. There are two reasons. Firstly, I usually end up paying out of my own pocket. And secondly, I usually manage to inspire or persuade people to accompany me on the journey.

But if you do manage to create a world, then those who grasp it will join in. Because they understand it.

The problem with us architects is that we try to make everything consumer friendly.

It’s the same with music.

If you try to appeal to consumers, you get pop music.

While on the subject of music, it’s a key feature of many of your projects. Are you a fan of the arts and music?

Well, I’d be the first to admit that I’m the world’s least musical person. But it was fascinating that the musicians in Blaibach said that this concert hall reminded them of a musical composition itself.

Based on everything you’ve told us, shouldn’t prior completion of a project be mandatory for admission to architectural guilds?

Yes, that’s an interesting idea. Aspiring architects should be required to build something or be able to present their philosophy. And in manner that’s easy to understand and clarifies what the outcome would be. The fact that the underlying philosophy has taken a back seat in our digitally saturated, non-material world over the past 20 years is problematic. It would appear all the more crucial to prove how mindsets had evolved.

What projects are you currently otherwise working on?

At the moment, it’s primarily the honeycomb project.

Oh right, we thought that had already been finished.

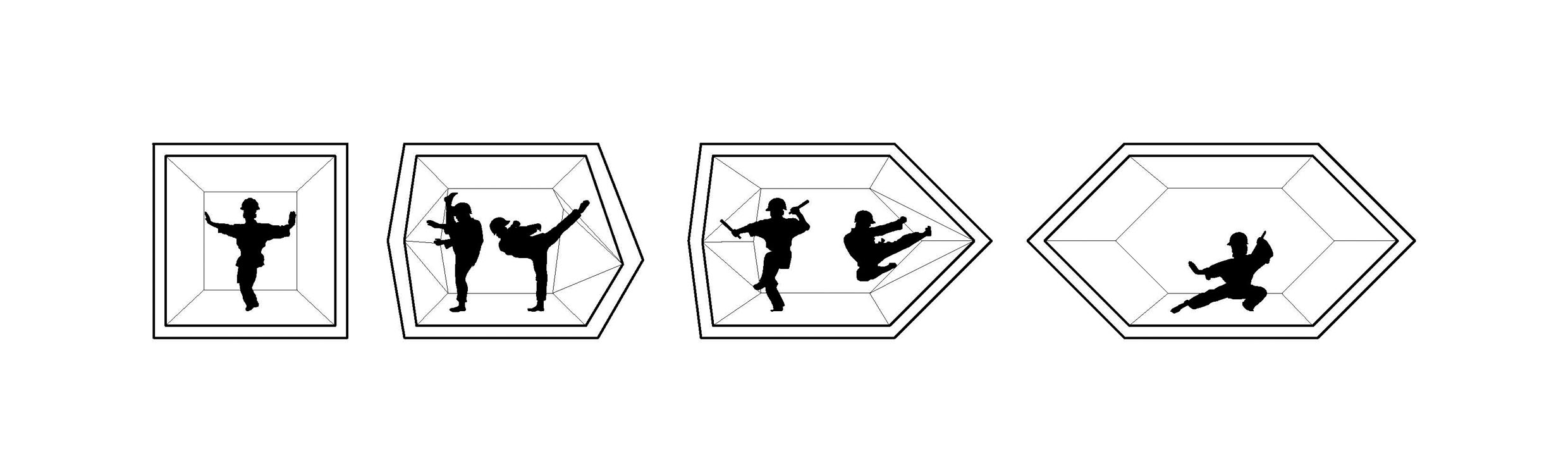

No. What you’re referring to is just the prototype. The module only consists of three elements with which you can build whole towns or cities. That’s actually what I’m exploring. In the first ten years of my studio, I developed urban visions for Europe and programmed architecture. I want to return to that, but with just one product. My honeycombs are a product that other architects can then use.

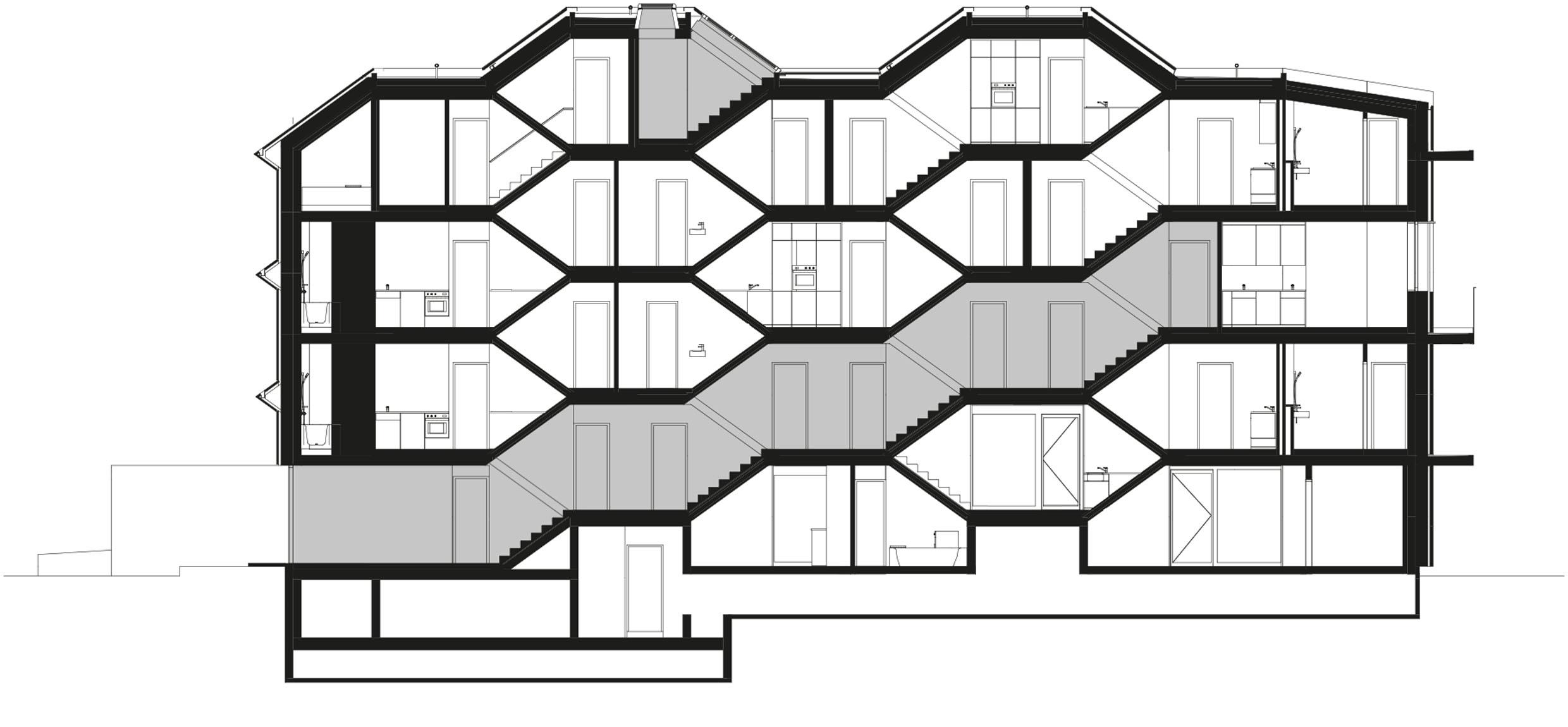

A company called MAMAWABE now develops the modules and produces them for modular construction methods. The building in Munich-Riem was a more conventional type. But I knew that you had to build one first to see how it worked in general and what the response was. When you study the 50 sq m apartments there, they look like 80 sq m ones. They are deceptively spacious, but the room volume is the same.

We give architects and society basic modules to apply, add to and combine. All based on our motto that we need disruption to end construction. Human beings have been living in boxes for 1,000 years. Modernism has done nothing to change that either. But is the box really the best we can do?

Living in honeycombs is simply wonderful and incredibly communicative. You can connect honeycombs and add staircases wherever you want. The honeycomb is like a piece of Swiss cheese that you can live in. It has niches where you can sit or lie and holes to stash things away in etc.

The clever part is also that, compared to normal houses, it’s easy to connect the modules. There are only a few elements – the wall, ceiling and a point where you click the pieces together and you’re done. I can build whole towns with these three elements. The modules are very simple, replaceable and recyclable. The expanded clay used has better acoustic characteristics. It absorbs moisture and is way more soundproof than standard concrete. And it’s more sustainable of course.

The honeycombs are made in one month, cost comparatively less and aren’t built but delivered to the building site ready for use. In other words, they come as prefabricated single parts complete with bathroom, lift, surface finishes, the electrics and connections. What’s more, compared with a normal “box”, you can transport vastly more square metres of living space. Which also cuts the carbon footprint.

The honeycombs can become standalone new builds. But they can also be added to existing buildings, or single modules can be used as street furniture or bus stops.

And perhaps best of all – forests, which our towns and cities currently lack, can grow on the honeycombs.

How do you plan to implement the project exactly?

I founded the company, but have since sold it. However, I’m still a collaborative partner and own licences.

Does that mean you’re setting up production at the moment? Or are you issuing licenses for others, so to construction companies?

That’s not been fully decided yet. Initially, to allow the construction of more buildings, we’ll definitely be producing the honeycomb ourselves. It’s possible that the product will be issued on a licencing basis in future. I’ve spent five years on the product non stop, so I want to run the show for as long as possible so that the market launch is perfect.

How did you end up working on the Wogeno project in Munich-Riem?

I just contacted the housing cooperative and presented the idea. Pleasingly, an audience of 70 came and these people then decided whether it would be built. And, by the way, they voted unanimously in its favour. But you can also see where the problem sometimes lies.

Conventional property developers often reject buildings with no track record because they don’t know whether people will buy them.

Which is why some ideas don’t even reach the market in the first place.

In general, we need more construction by housing cooperatives in Germany. Countries like Switzerland are a step ahead.

I’m counting on manufacturing based on economies of scale so that we can cut prices, but still achieve better quality than in standard apartments.

We’ll cross our fingers and be keeping a keen eye on progress. Thanks for such an enlightening interview.

Peter Haimerl, born in Eben in the Bavarian Forest in 1961, is an architect and has had his own studio since 1991. He lectured in Munich, Braunschweig, Kassel, and Linz, and has been a member of the Berlin Academy of Arts since 2018 and the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts since 2022. His oeuvre deliberately transcends the boundaries of conventional architecture. His interdisciplinary processes spawn unconventional, innovative concepts that marry architecture with art, technology, and society.

Interview: Jan Hamer & Ulrich Stefan Knoll

Image credits: Portrait photo Peter Haimerl © Edward Beierle (Cover), Schedlberg © Edward Beierle (1-6), New Bayerwald project Jetzing © peter haimerl . architektur (7, 8, 10, 11), Art stallation from beierle.goerlich with Benita Meißner © peter haimerl . architektur (9), Castle of Air, Cincinnati © peter haimerl . architektur (12) Concert hall Blaibach © Edward Beierle (13-16), Concert hall Blaibach © peter haimerl . architektur (17), Haus Marteau © Edward Beierle (18-20), Schedlberg © Edward Beierle (21), Wabenhaus © Edward Beierle (22, 24-26), Wabenhaus © peter haimerl . architektur (23, 27)

0 Comments