Dialectical Materialism in Construction

In the first part of our series on circular economy, urban mining and cradle to cradle, we start with a current overview of the transition in the building sector.

Climate change and resource scarcity demand a transition in the building sector: We must reuse valuable materials from existing structures. The fundamental principles are circular economy, urban mining and cradle to cradle. The first steps towards this transition have already been taken.

The buildings and construction sector is responsible for 37 per cent of global emissions, making it by far the largest emitter of greenhouse gases, as stated in a United Nations report published in September 2023. For a long time, the focus has been on how operational carbon emissions of buildings can be reduced, such as those caused by heating, cooling and lighting. The recently much-discussed Building Energy Act is another step in this direction. Much still needs to happen here, but initial progress can be noted. According to the UN report, forecasts suggest that these emissions will decrease from 75 to 50 per cent in the coming decades.

However, solutions to reduce carbon emissions embodied in buildings lag behind. Particularly, the production and use of materials like cement, steel and aluminium cause a significant carbon footprint. The urgently needed building transition faces major structural hurdles. Nevertheless, there are promising concepts, and there are already initial projects that impress in term of their design.

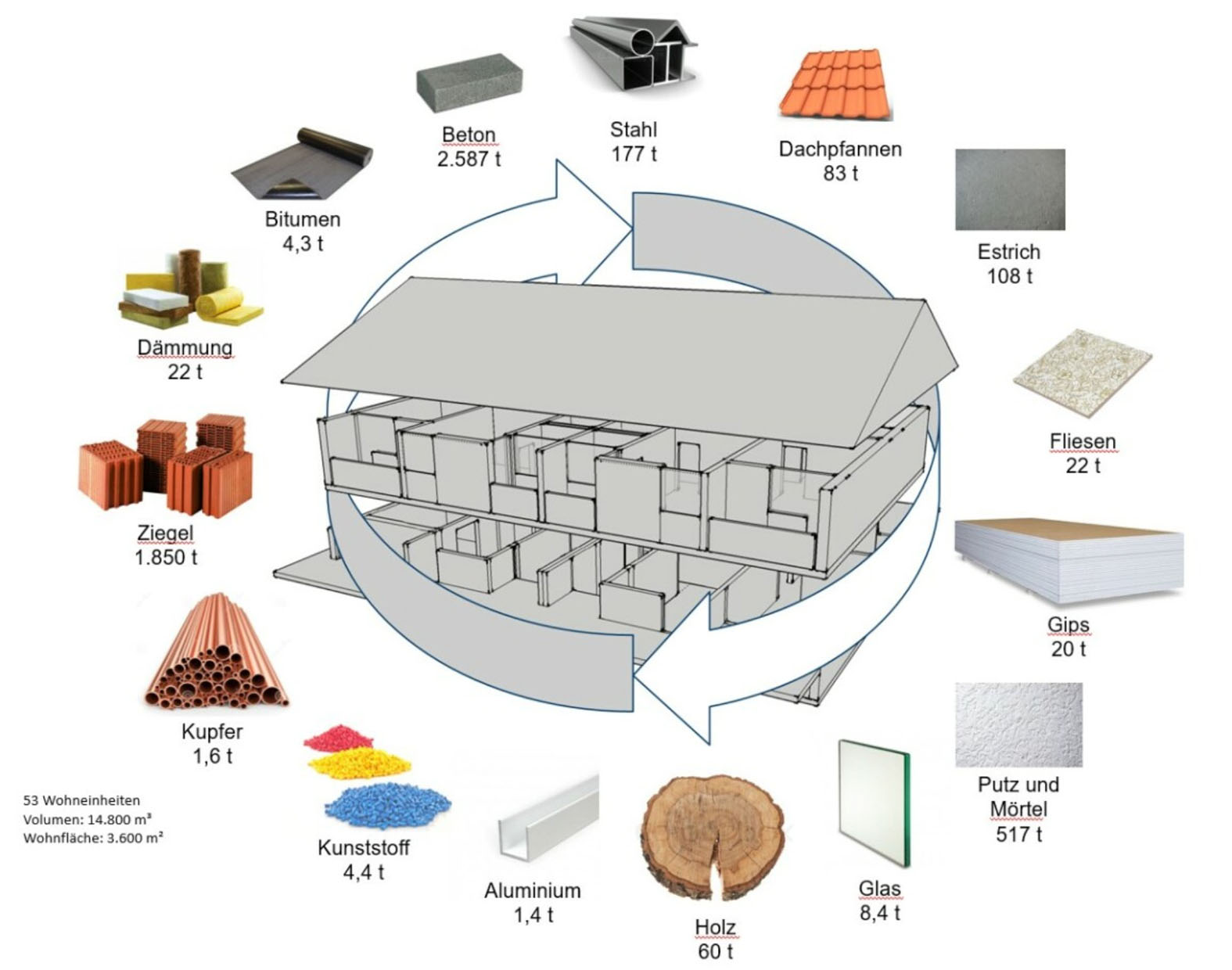

One thing we don’t lack is building material because our existing structures harbour enormous treasures — which we have been squandering so far. In Germany alone, around 900 million tonnes of waste are produced annually. Nearly 55 per cent of this is construction and demolition waste, of which only about 34 per cent is recycled. Valuable metals and building minerals in particular are often stored in infrastructures and buildings for long periods, sometimes over decades. As a result, enormous amounts of material have accumulated, which harbour great potential as a future source of secondary raw materials. That’s why the term urban mining is used in this context, the city as a mine full of resources.

To mine on a large scale in the urban mine, a building material register is needed, specifying exactly what materials are available and in what quality. The city of Heidelberg takes the first step in this process and records its inventory. The municipality uses a so-called Urban Mining Screener. The programme is intended to estimate the material composition based on building data such as location, year of construction, building volume or building type and produce results at the touch of a button.

The first investigation focuses on a former housing estate for US Army members. The Patrick Henry Village covers an area of about 100 hectares and could accommodate 10,000 people and provide 5,000 new jobs. Currently, there are still 325 buildings on the site. These are to be either demolished or refurbished — thus representing a valuable raw material store. According to the Urban Mining Screener, the neighbourhood holds 465,884 tonnes of material waiting to be reused, about half of which is concrete, a fifth bricks and around five per cent metals.

With a consistently implemented circular economy, such stocks would be available on the building materials market in the future, just like new products to date. A central and easily accessible material and component catalogue, in which available products are catalogued and retrievable, would contain all the necessary component information. For such a catalogue to be maintained, the new or, better still, recycled construction sectors would also have to engage: when a building is constructed, ideally all information about the products should be submitted in the form of a building file.

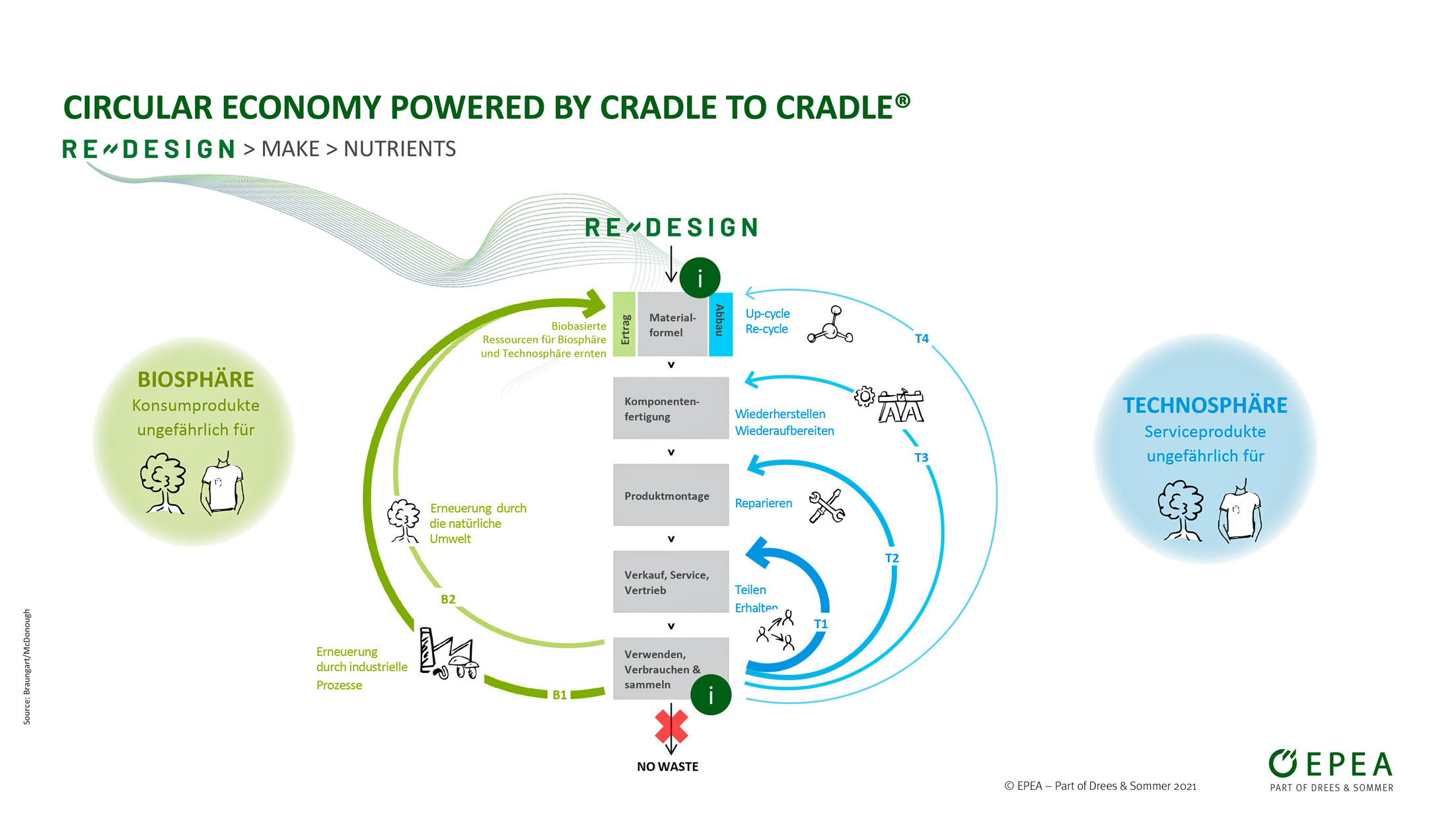

The goal is clear: In the future, we will consistently build from existing materials or renewable resources such as clay or wood — even flax and fungus are feasible. The composition of buildings is also documented in material passports for later reuse elsewhere. This would realise the Cradle to Cradle principle, developed by eco-pioneer and chemist Michael Braungart together with the American architect William McDonough. Cradle to Cradle is based on biological cycles that leave no non-recyclable waste. Climate- and resource-neutral construction is achievable. Already today. In the next episodes of this series, we will present some best-practice examples and show the steps architects and clients can already take.

Author: Lars Klaaßen, January 2024

About the author: Lars Klaaßen, journalist, has been working as a freelance author and editor — among others for taz, Süddeutsche Zeitung, Deutsches Architektenblatt and scientific institutions — since 1989. He specialises in the fields of architecture and urban development, construction and housing as well as energy transition and climate change. www.medienbuero-mitte.de

Picture credits:

© Avel Chuklanov / Unsplash (Titelfoto); © EPEA – Part of Drees & Sommer 2021 – Quelle: Braungart/McDonough (1); © EPEA – Part of Drees & Sommer – Materielle Zusammensetzung Mehrfamilienhaus München Baujahr 1962 (in Tonnen (t)) – Quelle: Matthias Heinrich, EPEA (2)

0 Comments