Holidays. The best time of the year.

When did we actually start taking holidays? And how has the concept of ‘free’ time changed over the centuries? A short (cultural) history.

Holidays at last – the best time of the year. Most people look forward to having time off when they can simply relax without having to do anything. What we take for granted was unthinkable two hundred years ago – although the (cultural) history of holidays began in ancient times, it has been retold again and again over the centuries.

The forerunners of holidays

Even in Greek and Roman cultures, there were forerunners of the holiday, time to take part in public celebrations or religious ceremonies. In the Middle Ages, ‘urloup’ (in Middle High German, equivalent to ‘exemption from duty’ or ‘permission’) meant an authorised absence from work or other obligations – a privilege reserved for a few (male) members of society. However, this leave of absence had nothing to do with holidays as we understand them today. Due to the feudal social structures and the resulting relationships of dependency, it was impossible to be exempted from work for private matters. The trade journeys or pilgrimages that were common at the time were not for pleasure – and were also extremely arduous and often life-threatening.

From educational trips to recreational holidays

The era of travelling began in the 16th and 17th centuries with research and educational journeys – but these also served a purpose and were not seen as leisure time. In the 18th century, it became fashionable for European aristocrats and wealthy commoners to send their sons on a ‘Grand Tour’: The young men travelled to Rome, Venice, Florence, Nice, Paris or Vienna by coach and with their travelling trunk in order to educate themselves culturally. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who advocated travelling for the sake of travelling, was at the forefront: ‘One does not travel in order to arrive, but in order to travel.’ Even in those days, many wealthy aristocrats spent the summer months at spas or travelling on their own estates. Civil servants and senior employees were given unpaid holidays and schools, universities and courts were also closed in the summer. Everyone else – whether farmers, craftsmen or simple labourers – could neither treat themselves to a break nor did they have the necessary means to afford a trip.

Wanderlust, Thomas Cook and the right to a holiday

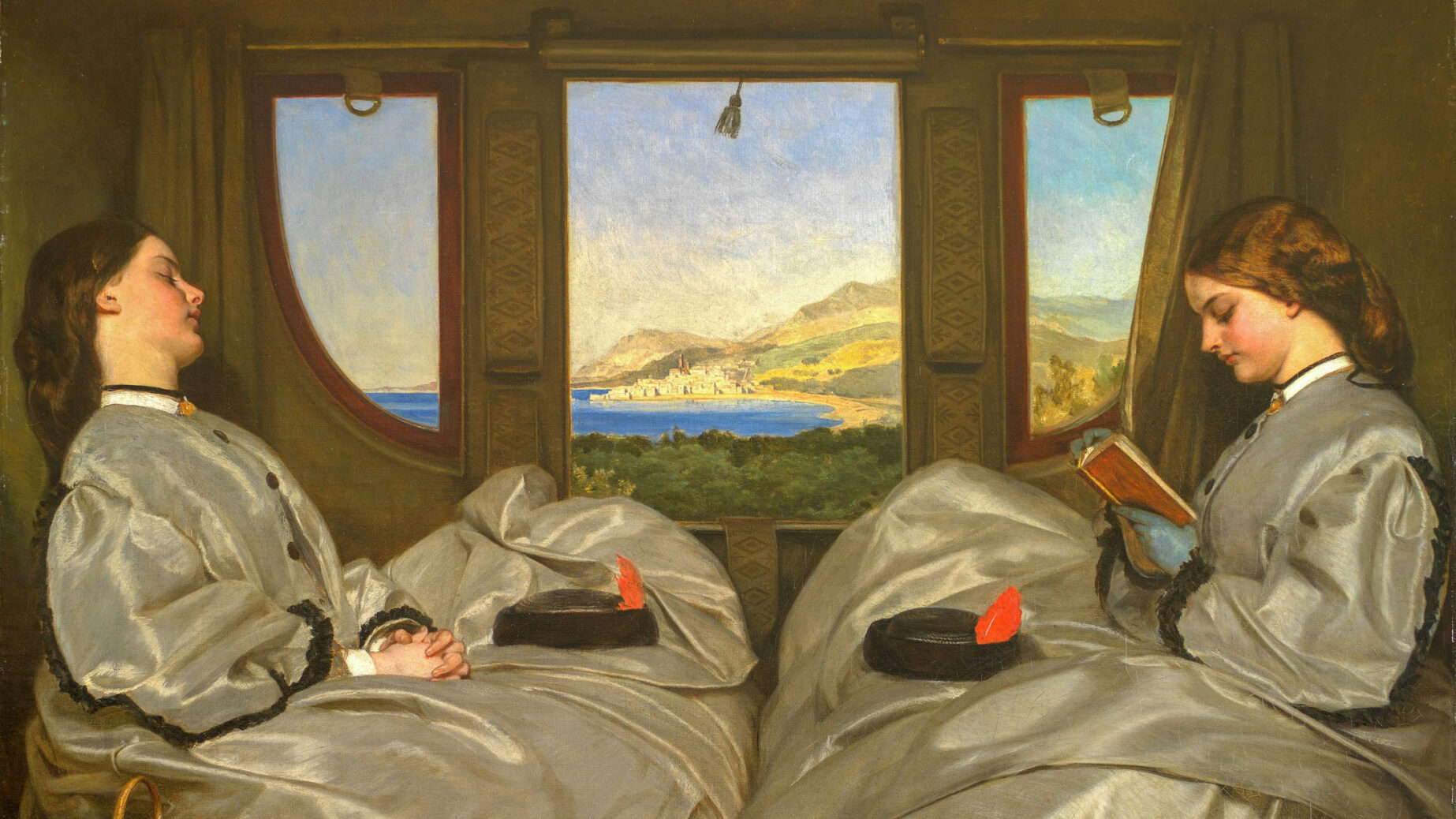

In the 19th century, the importance of travel changed – and with the advent of industrialisation, so did the understanding of (recreational) holidays. In the Romantic era, many people discovered their love of nature: Hiking took on a new significance, the Alps were discovered as a holiday destination, skiing was ‘invented’ and the term ‘wanderlust’ was coined. The Englishman Thomas Cook, a Baptist missionary who originally offered rail journeys for followers of the temperance movement, organised the first package tours, the destinations of which became increasingly unusual over time. Whether by Orient Express to Istanbul or by steamship to Egypt: People wanted to experience something, travelling was now for pleasure – and thus for the first time comes closer to our current understanding of holiday travel. For the general population, however, holidays and travel initially remained a distant dream. It was not until 1903 that the Central Association of German Brewery Workers was able to push through a paid holiday entitlement – giving them three days off per year. Another twenty years later, the trade unions were able to enforce an entitlement to holiday with continued payment of wages. But even then, for most people it was no more than a Sunday Kaffeefahrt [promotional trip where passengers are served coffee and are offered goods to buy] or a visit to the fair. Many trade unions and educational organisations organised cheap trips to the Rhine or to the seaside resorts on the North Sea or Baltic Sea that were popular with the wealthy middle classes.

From summer holidays to mass tourism

Finally, in the 1920s, travelling abroad was affordable even for well-paid employees – until the Great Depression put an end to this brief period. During the war years, holidays in Germany were designed to serve ideology through the ‘Kraft durch Freude’ [Strength through Joy’] tours. After that, Germans’ destinations tended to be in the low mountain ranges – not until the following years did holidays become more and more synonymous with travel, whether to nearby recreational areas for a summer retreat or to neighbouring countries. In the 1950s, tourism increasingly developed into a significant economic sector: The emergence of mass tourism meant that travel was now affordable for almost everyone – even if many could initially only afford a camping holiday. Italy soon became the most popular holiday destination for Germans – until the Balearic island of Majorca, still an insider tip in the 1960s, experienced a real travel boom. At that time, most people could not yet imagine travelling far away. One exception was the so-called ‘hippie trail’: a journey, mainly by hitchhiking and preferably as far as Asia, to gather spiritual experiences. In the decades that followed, air travel became increasingly cheaper and therefore more popular. The world seemed to become smaller, and the destinations had to be as exotic and prestigious as possible.

Holidays today: Everything is possible, nothing is a must.

Today, holidays are primarily a time of (active) relaxation. There are countless options: from package holidays to active or even extreme trips to wellness and cultural holidays or even a break at home. Holiday time, which is still limited in many countries, is now associated with so many expectations that one trip a year is often not enough. In addition to aspects of environmental and social compatibility, the focus is then on opportunities to gain new and authentic experiences in other cultures or to (re)discover oneself. For some years now, workation has also enjoyed great popularity thanks to mobile working methods.

So almost anything is possible on holiday these days – everything can be, nothing has to be done.

Text: Tina Barankay, May 2024

Photo: Birmingham Museums Trust / Unsplash

0 Comments