Free as Oscar

The South Tyrolean architect Martin Gruber allows his thoughts to fly, pushes back the horizon and meets Oscar Niemeyer at the Copacabana. An ode to the creative power of imagination.

“The new values in architecture are passion, empathy, imagination and freedom. We should love what we do. We should feel time, manage it well, inspire people and create meaning.“

Martin Gruber

Spreading the wings

As a child, I always wanted to be a tightrope walker. Actually, I was one: I loved balancing on the curb behind our house and did it every day on the way to school, while imagining a 100-metre abyss gaping below me on either side. In my imagination I managed to feel a real sense of vertigo and so I no longer looked at the ground while balancing, but spread my arms out as if they were wings, my gaze fixed firmly on the horizon. That’s how I felt free. On a curb.

Balance and horizon are connected. Gravity acts at right angles to it. It is a permanent constant in life, especially in building. It is the force that makes construction possible. Added to this are material and function, as far as the familiar parameters of archaic building are concerned. The new values in architecture are passion, empathy, imagination and freedom. We should love what we do. We should feel time, manage it well, inspire people and create meaning.

My home is Verdings. Living in the mountains means being exposed to gravity more than anywhere else: whether on a bike or on a toboggan – it’s either uphill or downhill. With or without effort. The people living in the mountains owe it to gravity that they literally hang on to every usable square metre of ground. They have a strong attachment to the place – perhaps this is one of the reasons why I was always drawn back home. The story of my place and its unique horizon is about distinctiveness: the dialect, the character of the people, the clouds over the village, the silhouette of the stone giants, where the sky begins.

Sport took me beyond my personal horizon: as a 14-year-old I qualified for the European Championships in natural track luge in Murmansk, above the Arctic Circle in Russia, in the historic year of 1989. This first great journey – I had never flown before – dissolved the line of the horizon I had known until then, gave it a different scale, a new depth. In that annus mirabilis, the Soviet empire collapsed. The poverty, chaos and darkness of Russia left a lasting impression on me. I will never forget how I gave an orange to a boy of the same age in Kandalaksha, and he began to eat it, peel and all.

Meeting with the master

Fifteen years and a few medals later, I was coach of the Brazilian Olympic team in four-man bobsleigh. We had qualified for the 2006 Olympic Games in Turin. That was the plan for the winter semester. The summer, on the other hand, was reserved for my great love: Architecture. Soft and sensual. Organic and self-confident, strong, beguiling and “unpossessable”. During a training camp for the bobsleigh team in Rio de Janeiro, I visited Niemeyer’s Casa das Canoas. White concrete in the dark green jungle, curved over a stone, over a pool. Weightless and free. It was humid, my shirt stuck to my damp skin, then the rain started. Vera Lúcia Cabreira, Oscar’s secretary and later his wife, watched me from the window and saw how much the house captivated me. She suggested I meet the master.

I arrived at the penthouse at 3940 Avenida Atlântica – with a view of the Sugar Loaf Mountain and Copacabana – right on time. Niemeyer’s assistant promised me an audience of no more than 5 minutes. It turned out to be 60 minutes and we laughed a lot, because I – then in my mid-thirties – was not prepared for some of the 97-year-old’s witty remarks on the subject of curves. The balance of forces was his answer to my question about the importance of symmetry. And indeed: Construction does not lie. Anyone who stands under Niemeyer’s boldly cantilevered buildings in Curitiba or Niterói is likely to sense their extraordinary constructive dimension. Construction is balance. Mirror forces compensate for each other, gravity is seemingly suspended. The resulting feeling of lightness and freedom shows in the most beautiful way that architecture can be the totality of proportion, material and idea.

I have a crystal-clear memory of Niemeyer’s argument against mental gravity, that force of habit that we best deal with through personality and ingenuity: “Architecture is a matter of dreams and fantasies, of generous curves, and wide and open spaces.” From then on, inspired by this grand masterly tenet and the lightness of Brazilian modernism, I wanted to design spaces that inspire, are free and integrate naturally with landscape and culture.

Open to the world

With this profound experience in my luggage and in my soul, I returned to Verdings, beyond the horizon that I can draw by heart. To the place where my grandfather left the farm to my father and he left it to me. I was allowed to anchor the farm architecturally in the present and to let the wisdom of yesterday continue to have an effect. I studied the centuries-old building rules of the Eisack Valley – functionally proven and outgrown by our mountain world.

verything was clear, coherent and right. But a part was missing. A part of “my” new world beyond the horizon: the salty breeze of the sea, the foreign diversity, the lightness of Brazilian modernity … The idea for a guesthouse came quite suddenly and intuitively. My wife, a native of Munich, and I thought it through together. We wanted to bring the whole world into our home – friends, acquaintances, personalities. And with them interesting conversations, precious moments.

Our farm is configured as a multi-generational house. We design our living space through family cohesion, appreciative interaction with people, animals and nature – embedded in an enriching, neighbourly context. Architecture and nature, rural lifestyle and hospitality mutually stimulate and inspire each other on our farm. For outsiders this makes the place a healing, inspiring space for recreation and self-development.

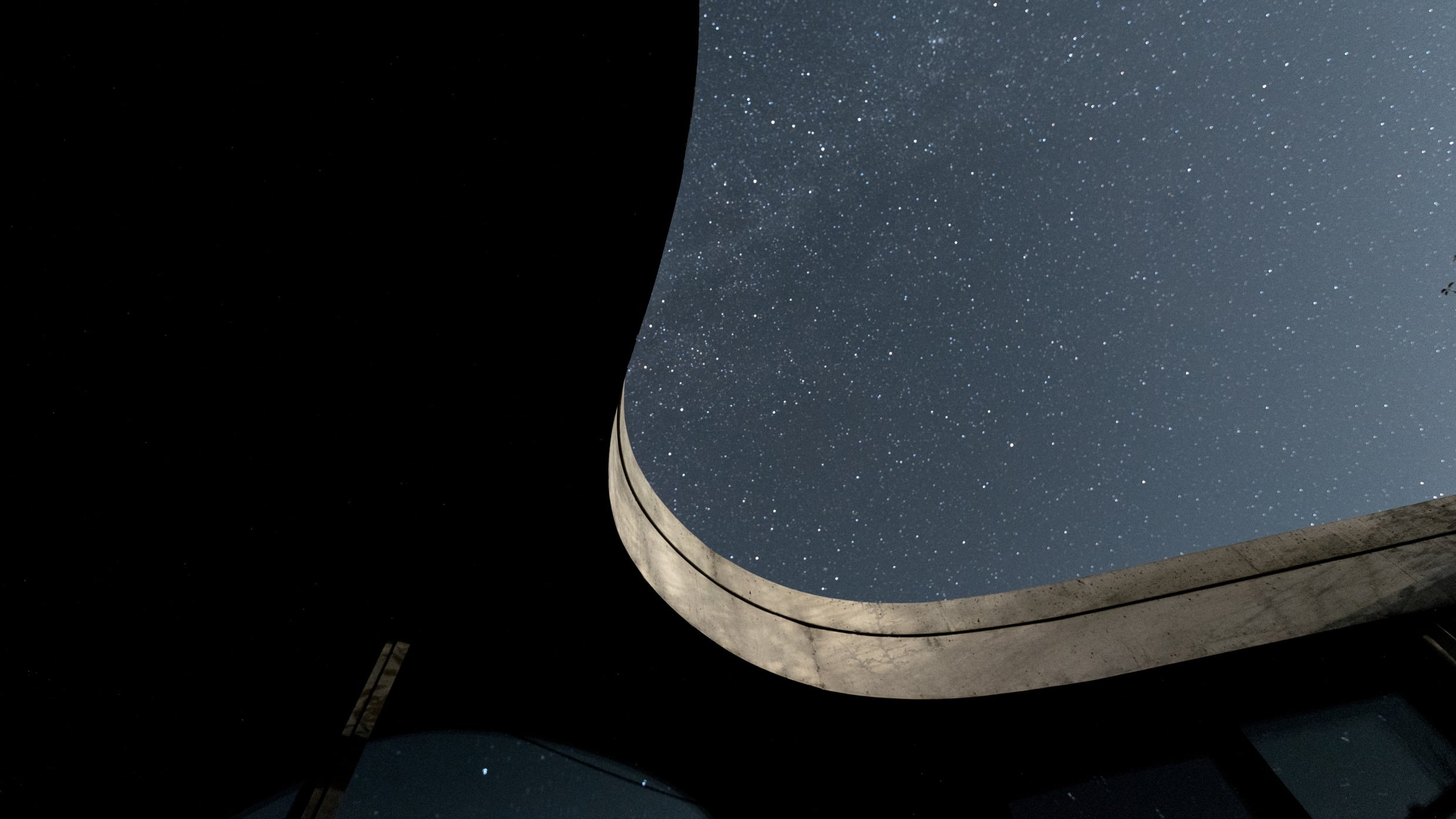

Freiform

Against this background and with this palette of values, I drew the Freiform, designed it lightly and buoyantly off the cuff. The result is a hybrid between a guesthouse and a nature observatory, a walk-in spatial sculpture that only developed its true qualities and meditative effect after its completion. The floor and ceiling were cast in concrete with the same shape, while the interior is dominated by solid oak and loden. A 20-metre-long glass façade encloses the organic building and it seems as if the landscape flows through it. The interior appears neutral and without a predefined concept of use. This creates the space to locate individual needs and priorities and to consciously shape the visitors’ holiday time. We only give our guests a little nudge by leaving out everything that could disturb their direct dialogue with nature. They will look in vain for a television in the Freiform, but they can look out into the distance at any time of day or night.

The Freiform is an expression of our attitude to life and we are happy and grateful that our guests are people who, like ourselves, resonate with the place, with its depth and originality. We value the encounter as equals; sympathies, synergies and friendships develop. We muse together about the connections between the weather and the gestation of bees, about old apple varieties, the pitfalls and joys of self-determination to do what we love. We sit on the terrace, exchange points of view and perspectives, and enjoy a good local white wine together. The world comes to us. Those are the truly sacred moments: when farm and world meet.

Now I live in inner balance in the midst of “my” mountains , when I look at the horizon, I feel neither homesickness nor wanderlust, all the pieces have come together. I have got to know myself better over the years, which has also allowed me to mature professionally. Inspired by my experiences and encounters abroad and as a result of the exchange with guests, insights and mental concepts form, which I take up as an architect and convert into new designs.

I like to think about the diverse life beyond the horizon – sometimes asking myself what is happening right now, at this very moment – in Rio, Moscow or Beijing. I feel both the global dimension and a great humility before the genius loci. I let all this flow into my current projects and feel that creative freedom is the greatest privilege of being an architect. Was it a coincidence that my current commission brought me to Ploseberg, 1850 metres above sea level, to where the horizon seems flat again, almost as if you were looking at the ocean off Ipanema? The distant view brings the mountain peaks closer together at their height.

When I first visited the building site, I drew buildings in the air, like a conductor speaking to a string orchestra. I felt the harmony, the spirit of the place – fragile and ephemeral – immediate and absolute. It was an attempt to touch landscape and building at the same time, my hand open to grasp this fleeting moment, the vision of the project. Quite automatically, I spread my arms, stretched them out towards the beauty and yearning, and for a moment it felt again as if I were balancing on the curb and … flying.

Author: Martin Gruber, born in 1975, is known for his striking hotel buildings and architecturally sophisticated designs. Together with his wife Anita Stare, he runs the family organic farm and the Freiform guesthouse in the South Tyrolean mountain village of Verdings.

Photos: © Tobias Kaser (all but Casa das Canoas – © Martin Gruber)

Source: The article is part of our publication Raum & Zeit ⎜Space & Time

2 Comments

Wäre ich frei wie ein Vogel, dann wäre das mein perfektes Nest! Wahnsinn Komplimente an Martin👌

Schöne Story Vielleicht darf ich mir einmal persönlich vorbeikommen. Lg

Die Renaissance war vielleicht eine schöne Zeit, ist aber nach allem dem Formulierer dieses Satzes Bekannten, vorbei – und mit ihr der sinnstiftende Anspruch der Architekten, der fatal, weil sich nicht als dienend begreifend, auch durch die Zeilen dieses schönen Beitrags, wie kaschiert immer, schimmert.