What is truly simple – and what only appears to be? A conversation with Florian Nagler

In one of our recent Friday talks, we spoke with Prof. Nagler about simplicity in building and on holiday, about experimental research buildings, the “Building Type E” and the conversion of shipping containers into mobile artist studios.

Good evening, Professor Nagler – where are we reaching you right now?

I happen to be back in Bad Aibling at the moment, visiting one of our clients, with whom I developed three research buildings.

We’ve had a connection for quite some time through the Tannerhof, which we feature on HOLIDAYARCHITECTURE. How exactly did this long-standing collaboration with the hotel begin – one that has just entered a new chapter with the opening of the Badeharpfe?

Tannerhof: From the outset, we were able to aim for using simple means.

I met Burgi von Mengershausen and Roger Brandes from Tannerhof through the painter Peter Lang, a mutual friend. He transferred to my secondary school back in the day for the advanced art course, but before that he had gone to the same school as Burgi and Roger. Much later, he made the connection and told them: If you’re going to build something – build it with Florian!

At that time, was simple or pared-down building already a core focus of your work – or did that only become a central part of your approach later on?

The topic or question has preoccupied me from the very beginning. Around the same time, I built a cowshed and the visitor centre for the Dachau concentration camp memorial site.

Those two projects always stand side by side in my mind: the cowshed, which was built as simply as it looks – and the memorial building, which at first glance appears very simple, but is actually extremely elaborate in technical terms. And that’s the spectrum I keep coming back to: What is truly simple – and what only appears to be?

At the Tannerhof, it was clear from the very beginning that the clients were never particularly interested in pushing technical boundaries. From the outset, we were able to aim for using simple means – so in that sense, the Tannerhof was a great project for exploring those ideas too.

At the same time, we were working on completely different projects that involved very demanding specifications and extensive use of technology. At some point, we realised for ourselves that this wasn’t how we want to keep building. We began to ask whether we could achieve our goals by resorting more to architectural means.

For the Tannerhof, there has been a very long-standing collaboration, spanning several construction phases. Was there a master plan at the outset?

We actually started with the task of developing an overall concept – which we kept adjusting over time. Partly because we got to know the Tannerhof better and better as the years went on, and partly because the concept, which was designed to last for years and decades, had to be repeatedly measured against what was financially feasible. So some ideas were never realised, or were postponed. The current project – the Badeharpfe – was also the result of a long process.

The original idea was much bigger – a fairly large building with a pool and sauna, along with the conversion of the old bathhouse. But we couldn’t afford it – which, in hindsight, was actually a good thing.

So we reduced the whole concept down to the Harpfe, which compensates for everything that hadn’t been working optimally in recent years: a proper fitness room, an expanded sauna area and a lovely relaxation space. That’s really all that was needed – so in that sense, it’s a success story of reduction.

In an interview with Burgi von Mengershausen, you mentioned a small pond that you think could be improved in future?

Yes, exactly. There’s a small pond above the buildings, with a spring and a little wooden deck. It’s a wonderful spot, but there’s potential to do more with it.

I actually thought the place was perfect as it is – simple and a natural transition into the open landscape. But of course, it would be interesting to hear how you would reimagine it.

It’s not about making architectural changes to this place. I just think it could be better integrated into everyday life at the Tannerhof. That might be a question of accessibility. In any case, it could be brought more into the awareness of the guests.

The studio had to fit inside a standard 20-foot shipping container.

Let’s turn to a different topic. In your portfolio. I came across a project in Patagonia – some sort of self-assembly container house for an artist. What’s the story behind it?

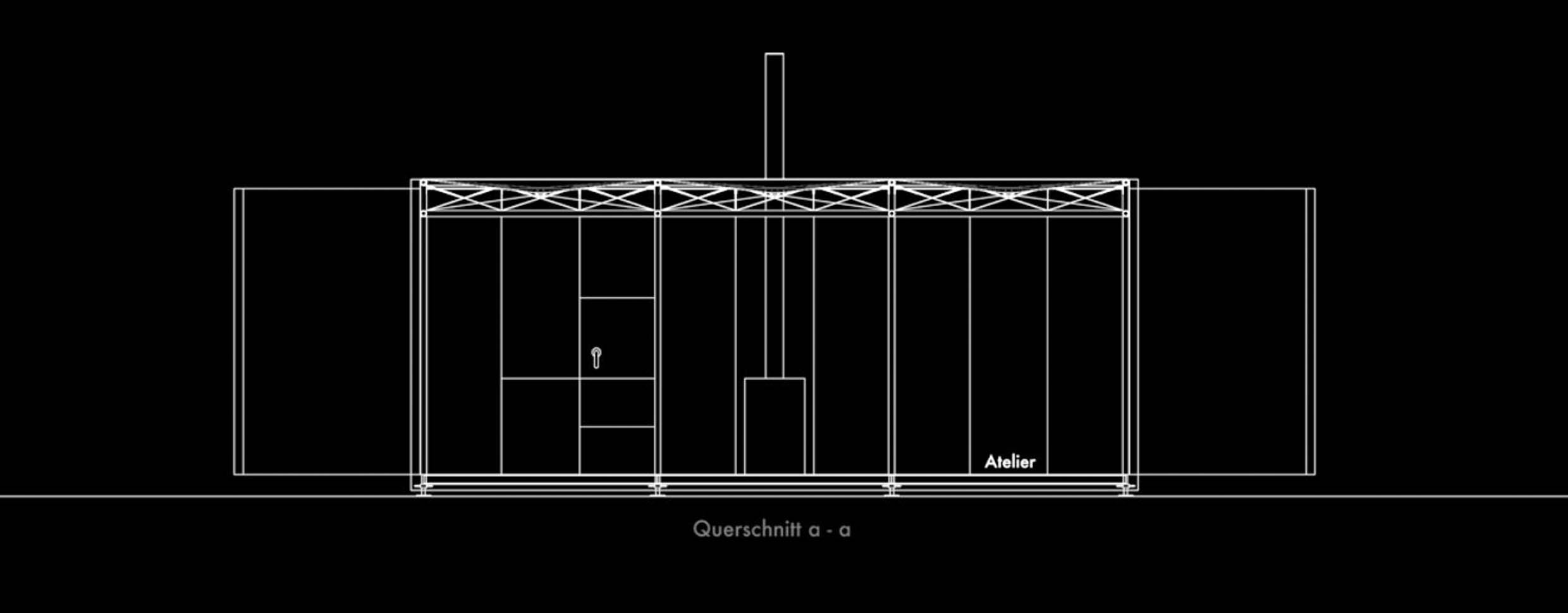

Ah, you must mean the PRC (Peters Reise Container – Peter’s Travel Container) I designed for Peter Lang’s work projects! He wanted a mobile studio that would allow him to travel the world and paint en plein air, even in remote locations.

He had a few specifications: the studio had to fit inside a standard 20-foot shipping container, the usable studio space should be at least 60 square metres, and he wanted to carry 300 square metres of canvas. That alone took up about a third of the available space. And of course, it needed to provide facilities for sleeping, cooking and looking after oneself.

He took it to Patagonia where he spent six months painting. For me, it was an important project because in the planning and fit-out process, we spent a lot of time thinking together about what you really need in remote locations. In the end, we decided to reduce it down to the absolute minimum necessary for survival. There was a small wood-burning stove for cooking, a tarpaulin stretched over the top to collected rainwater, which drained into a cistern and was used to feed a camping shower. He had one solar panel that he used to power a radio.

Editor’s note: A 24-minute video about the travel container can be viewed here.

His conclusion when he returned: everything worked perfectly. Only in one respect were we completely mistaken. What we had considered the bare essentials, the absolute minimum, turned out to be far above what many people in the world actually get by with. Within a radius of several square kilometres, he had the most luxurious accommodation. You couldn’t have made the point any clearer: it’s us – people in Central Europe or North America – whose expectations and way of life consume the lion’s share of the world’s resources.

A beautiful setting really calms me down when I’m on holiday.

Which brings us straight to the subject of simple holidays. What matters to you when you are on holiday?

First and foremost, I think it’s important to realise that you often don’t have to travel very far to relax and have a good time-out. For me personally, the key thing is that the place is beautiful – a beautiful setting really calms me down when I’m on holiday. I don’t need much more than that.

That’s actually the same question that concerns us in our “normal” building work. First you have to ask: what does a “simple” holiday actually mean? And I do have the feeling that more and more people are realising that they are happy with less – or maybe even happier. I am convinced that this group of people is growing.

At the Tannerhof, for instance, we never succumbed to the temptation to work through a list of criteria for a star rating. Instead, we always did it the “Tannerhof way” – assuming that guests would recognise the quality. So there are things we deliberately didn’t include – things you’d need to tick the boxes for a 4- or 5-star hotel.

My impression is that you take a similar approach to curating your selection at HOLIDAYARCHITECTURE. Of course, I’m speaking entirely from my own perspective, but: I look at the places – and if I like what I see, I’m willing to overlook a lot. The most important thing is: it’s beautiful; I would like to sit there and relax. And if that’s the case, then everything’s wonderful – I don’t need much else.

Based on your experience with simpler ways of building – what lessons can be drawn for holiday accommodation? What insights are you and your clients gaining?

A lot of these buildings are conversion projects – and they benefit from the simplicity already inherent in these old structures: from the beauty of the materials and the tactile quality they bring.

The main takeaway from simple building is that we, as planners, need to start taking a few things seriously again – things that, really, everyone knows. For example: reducing the use of technology and working more with what architecture itself can do. Then: using as few construction details as possible – ideally building without any details at all. And of course: relying on solid construction so we gain thermal mass. Appropriately sized windows are another key aspect – although I realise that this may be difficult to convey from the perspective of HOLIDAYARCHITECTURE, since guests have come to expect expansive panoramic views. The size of windows is crucial for reducing our reliance on technology – it helps prevent overheating in summer and reduces heat loss in winter.

These are fundamental aspects – not all of them can be entirely transferred to holiday accommodation, but I’m convinced that even in the context of holiday architecture , things could be built in a much “simpler” way.

In the end, it’s about ensuring we can continue to build affordable housing in the future.

And surely the “Building Type E” would be helpful here – the initiative launched by the Bavarian Chamber of Architects. If I’m not mistaken, that’s not yet officially enshrined in building codes, right? I believe it’s still in the pilot phase…

That’s right. At the moment, there are 19 pilot projects running in Bavaria, with different timeframes and conditions. But I think that in the coming year, a few of them will be completed – and we’ll be able to reflect on the first findings and experiences.

Our research houses in Bad Aibling, which often get mentioned in this context, aren’t actually Building Type E projects – because we’re of the opinion that we complied with all the regulations there. At least as far as we know them – after all, no one can possibly keep track of all 3,600 technical building regulations.

As part of the research project, we did consider whether we could make recommendations about which regulations ought to be abolished, streamlined or rewritten. But we were completely overwhelmed by the sheer volume of rules. We had to realise that we couldn’t manage it – it was just too much. After all, there have been countless commissions that tried to roll back the regulatory framework. Yet every time, they ended up producing even more regulations than before.

The clever thing about the approach of the working group at the Bavarian Chamber of Architects on Building Type E is this: all the existing regulations remain valid, but at the same time it is made possible for planners and clients to agree that, while still complying with the building code and the Building Energy Act (GEG), they will not follow all of the technical standards, DIN norms and regulations, some of which have, over time, crept into the construction industry through the back door. Instead, they agree to develop their own solutions – and if these work, then that’s perfectly acceptable. That, I think, is a brilliant move.

For all those who are ready to build with less, this offers a real opportunity. In the end, it’s about ensuring we can continue to build affordable housing in the future. That’s why I support the Building Type E initiative wherever I can.

So that means, I could commission you for a project and we could agree on legally binding conditions between us?

Not quite – legally, things aren’t fully sorted out yet. There’s still a change to the German Civil Code (BGB) required. The core problem is that, up to now, you could be held liable simply for breaching a regulation – even if no actual damage occurred.

In other words: a defect is the deviation from the standard, not the damage itself.

That so-called “non-damaging defect” is something the current legal reform hopes to eliminate. If that succeeds, it would be a huge step forward. I think it would really re-energise everyone involved in construction if this sword of Damocles were gone. Of course, it will still take some time. But it’s a goal of the current German government to make it happen.

One more question about the research houses in Bad Aibling: is there a final report yet?

Yes. The monitoring lasted exactly two years, and there’s a full research report – several hundred pages long – available on our website. There’s also a concise summary in the Bauwelt magazine.

Right now, we’re already working on a second series of research houses in Bad Aibling – this time with three timber-earth hybrid buildings, through which we’re aiming to significantly reduce the use of concrete, even compared to the first series.

And how does the developer B&O assess the results?

They’ve really taken to the idea of research. And for us as architects, too, it’s become a clear goal to apply the principles of simple building in our office projects from now on.

We also aim to transfer what we’ve learned to other building typologies – and to other building classes. We’re working on that. We’ve already completed a museum and a kindergarten, and now we want to move into higher building classes, like class 4 and 5. B&O, as developers, are doing much the same: they’re continuing to evolve and apply the findings from the research projects.

So that probably means moving more toward timber construction?

Yes, B&O tend to build in timber. If you look at the three houses in the first series, it’s clear that the insulated concrete house isn’t the solution for the future. Cement production uses far too much energy, and the life cycle assessment of cement and concrete is simply too poor.

That said, we’ll continue to use concrete in many areas. But it makes a lot of sense to think about how we can reduce its use, because these resources aren’t infinite. Instead, we need to clarify whether we can replace concrete with renewable materials.

In my opinion, the way we planned and built the brick house and the timber house in the series shows that it is possible to build houses that are both attractive and economical, and also very affordable – with a clear conscience.

So now all that’s needed is for the Building Type E legislation to be passed by the Federal Ministry of Justice to help bring the idea to a wider audience? That’s still pending due to the change in government, right?

Exactly. I really hope it happens soon – I’d love to be able to deviate legally from DIN standards for once (everyone laughs).

But seriously: we shouldn’t be kidding ourselves. It also means that, in certain situations, you’ll be taking on more responsibility if you can’t completely cover yourself. Still, I’d really love to get back to developing details that arise purely from structural and functional requirements – maybe from an aesthetic aspect – rather than against the backdrop of 30 sometimes contradictory regulations that have to be laboriously reconciled. That’s how it normally works at the moment. I think it would be a completely different way of working – and one that would be much more enjoyable.

The container has to be sized in such a way that one person can set everything up and take it down.

Absolutely! I would like to come back to the travel container… does it still exist, has it continued its journey?

Jes, it has. At the moment, it’s parked next to Peter’s studio in Gleisenberg, near the Czech border. And every now and then, he still takes it with him on his travels. He has taken it to Iceland twice, to Russia and to the Austrian Alps. And here’s a funny story: he had an exhibition in Ludwigshafen, and the container was placed behind the museum. That’s the one place where Peter was most afraid. In Patagonia or other places, this was never really a problem, but in Ludwigshafen he was really scared in his own container.

How exactly does the container and the module work, and how is it set up?

There’s a little guide for how to set it up. It’s what’s called a Full Side Access container, which means one of the long sides can be opened completely. It has four hinged panels that fold out to form additional spaces on both the left and right of the container. One side houses the shower, the other creates a sheltered entrance area. The open long side is where you attach the studio module. Of course, all the components have to fit inside the container, and they have to be sized in such a way that one person can set everything up and take it down – including the tarpaulin roof.

A wonderful project – and in a way, timeless. The idea of a house that travels is beautiful. Have you designed any other buildings that one can experience as a guest?

No, not really. With holiday homes, it’s usually the case that they are first built as holiday homes, and then the clients decide to move in themselves.

Well, that’s what good architecture does – and it’s a compliment to the architect. So where are you going on holiday next?

Oh, I don’t know yet. It’s not that easy, because I always want to go on holidays in the north – and my wife always wants to go south. If it were up to me: I’d love to visit the Curonian Spit one day.

It’s supposed to be very beautiful there. If you happen to discover a great holiday home that would suit our portfolio – do let us know.

Sure, I’d be happy to do that.

Thank you so much for this inspiring conversation, Professor Nagler!

After training as a carpenter, Professor Florian Nagler studied architecture at the University of Kaiserslautern. In 1996, he founded his own architecture firm, which he has run together with his wife Barbara since 2001. He has held guest and interim professorships at the University of Wuppertal, the Royal Danish Academy in Copenhagen and the Stuttgart University of Applied Sciences. Professor Nagler is a founding member of the Federal Foundation of Baukultur (Bundesstiftung Baukultur) and has been a member of the Academy of Arts (Architecture Section) in Berlin and the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts since 2010. That same year, he was appointed Chair of School of Engineering and Design at the Technical University of Munich. The chair focuses on the connection between design and construction and the translation of analytical studies into concrete built projects. Central to this is the physical presence of the structures. Research concentrates on the idea of “building simply”, aiming to simplify the construction process, and is closely linked to projects developed within his own architecture office.

Interview: The interview was conducted by Jan Hamer and Ulrich Stefan Knoll.

Photo credits: Prof. Florian Nagler © Johanna Nagler (Cover photo), Badeharpfe at Tannerhof © Sebastian Schels (1), Prof. Florian Nagler and Burgi von Mengershausen © Micol Krause (2), View Tannerhof © Hansi Heckmair (3), Cowshed Thankirchen © Florian Nagler (4), Dachau concentration Memorial site © Stefan Müller-Naumann (5-7), Tannerhof © Rainer Hoffmann (8, 10), © Hansi Heckmair (9), Badeharpfe at Tannerhof © Sebastian Schels (11-13), Pond at Tannerhof © Office Enno Schramm (14), Travel Container PRC © Private Archive Peter Lang (15-18, 21), © Florian Nagler Architekten (19, 20, 22), Tannerhof © Rainer Hofmann (23), © Hansi Heckmair (24), © Ann-Kathrin Singer (25), Research houses Bad Aibling (1. series) © Sebastian Schels (26-29), Research houses Bad Aibling (2. series) © Sebastian Schels (30-32), Travel Container PRC © Private Archive Peter Lang (33-38)

0 Comments